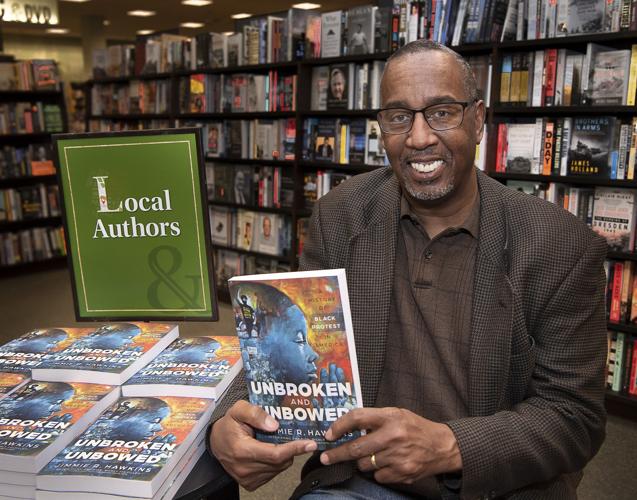

Five Questions with Author Jimmie Hawkins

Frederick resident the Rev. Jimmie Ray Hawkins is the author of “Unbroken and Unbowed: A History of Black Protest in America,” published in February. An ordained minister for over 25 years, Hawkins currently serves as the director of the Presbyterian Church (USA) Office of Public Witness in Washington, D.C.

He recently spoke with 72 Hours about his new book, which tells the story of African and African-American resistance to oppression and racism from the earliest days of enslavement through the George Floyd protests of 2020.

Hawkins will hold a book signing at Barnes & Noble in Francis Scott Key Mall at noon on March 19.

Can you share what led you to write a book on the history of Black protest?

I grew up in the Black church, so I’ve always heard talk about support for the civil rights movement and for the justice movement in the community. That has never been something that’s separate from my understanding of being a Christian and a person of faith.

What really triggered the book was Colin Kaepernick, his protest. He was getting a lot of criticism that he was unpatriotic. I wanted to make a response basically to defend what he was doing, not only politically but as a movement of faith for me as well.

I think a subset motivation is I find there’s not a lot information Americans have about Black history. Basically, all the conversations revolve around slavery and Jim Crow. I want to talk about Black experience as a whole and how diverse it has been, how multilayered it’s been.

What was your approach to organizing such a long history?

I started very simply, wanting to talk about how Black protest should be viewed through a patriotic lens. I started to notice that Black protest was linked closely with Black identity, so the book is really divided into five sections, where I break them into time periods under each Black identity under that period.

During [the early period of] slavery, the identity was an African identity. That’s followed by the “colored” identity during the abolitionist period wherein Frederick Douglass and others dropped an African identity. That’s followed by the “negro” identity during the 1960s and 1970s, when Martin Luther King Jr. and other civil rights leaders referred to themselves as “negroes.” And that’s followed by “Black” in the ’80s with the Black power movement. And today since the ’80s, we primarily refer to ourselves as African American.

Are there any instances of protest that stand out in your mind as pivotal to the history?

There are two I always point out, and these are two that are very common: the abolitionist movement and the civil rights movement.

The abolitionist movement was in many ways empowered by the ideology of the American Revolution. Writers such as Frederick Douglass talked about the hypocrisy of the nation, about how could you talk about freedom when you’re enslaving millions of Black people.

And then the civil rights movement, what it did was — I firmly believe this — it altered the consciousness of the nation concerning race. I think for the first time, the country began to turn against white supremacy. People were shocked by the things that were happening throughout the South. I think it really became a self-awareness on the part of this country. Even racists say “I’m not a racist” now. It’s really turned the way America views itself along racial lines.

Does your book touch on the history of Black protest in Maryland?

I talk about education as a form of protest, and I talk about Frederick. It was late to the establishment of a Black school, and the first school I think was Lincoln High School. There was not a lot of information [in my book], but there were a couple of schools that came out of Lincoln in Frederick.

What are the main lessons you hope readers will take away from your book?

One of the big lessons of the book, I think, is that while many people talk about the lack of Black progress, Black progress has been halted in this country by legalized discrimination. There was legislation from federal and state government to keep Black people in their place once slavery was over. So I hope [my readers] will get a better sensitivity to the totality of the Black story.

Also, to inspire other marginalized communities to tell their own stories, for every racial and ethnic group to tell their story, how they have worked as part of the American experience.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.